By the time Claire Abernathy was 14 years old, her body had been permanently and surgically altered by medical professionals who insisted medical transition was the solution to her gender confusion.

Before she had even started high school, her chest, which she had bound tightly in an attempt to flatten what her body naturally developed, was surgically removed in a double mastectomy after just one 15-minute consultation. Her voice permanently dropped due to testosterone injections. And her developing sense of self as a young teenager was lost beneath a fog of medications, ideology, and manipulation.

“I felt like this is what I needed,” Claire said of the treatments in an exclusive interview with IW Features. “If I was really trans, this is what I would do… This is what you need to do to treat gender dysphoria. This is what trans people do.”

Claire’s journey into the medicalized world of gender ideology began when she was just a child. After experiencing near-precocious puberty, Claire recalled being perceived by others as a young woman when she was still very much a little girl, which worsened the discomfort in her body she already felt.

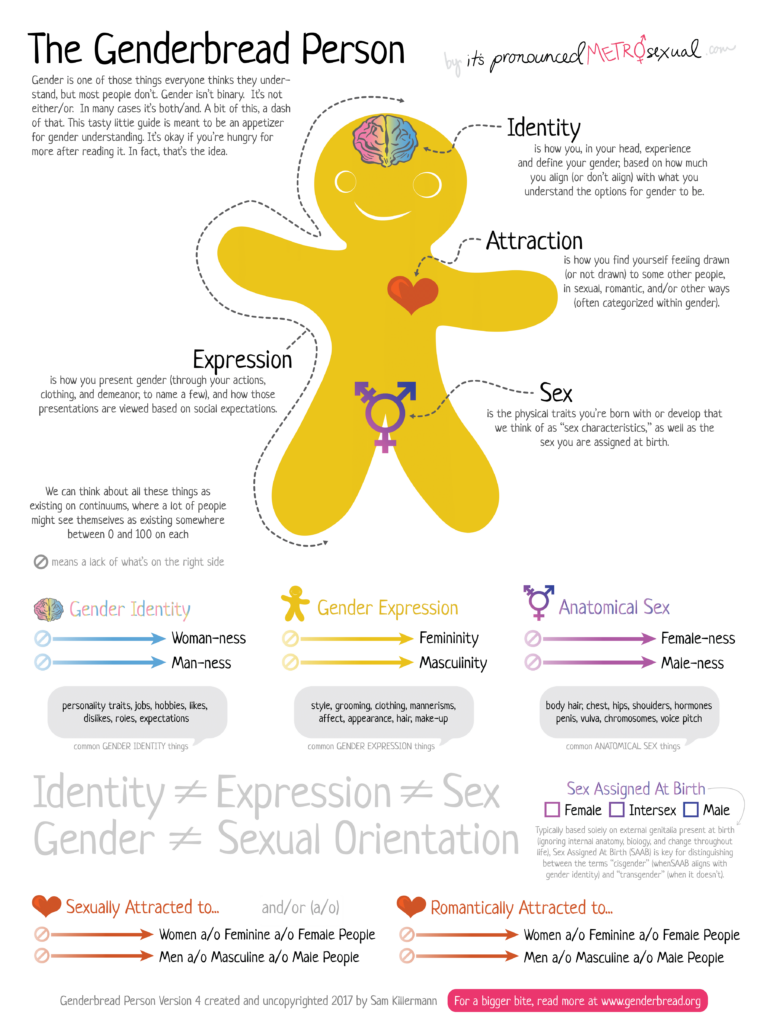

She said she was first introduced to gender ideology online –– specifically on Instagram and Tumblr, which are notoriously common breeding grounds for youth ideological manipulation –– and later in a school sex ed class in middle school through the “genderbread person.”

At age 12, she began seeing a therapist “specialized in the gender field” who, Claire said, “made my parents feel very small, like they didn’t know their own child.” The therapist warned her parents that failing to affirm Claire in her gender confusion would be abusive.

For Claire’s mother, Carrie Abernathy, those words were paralyzing. “If my child is going to kill herself if I don’t affirm her, I’m going to do whatever I have to do to save my child’s life,” she said. “That was kind of a no-brainer.”

Within months, medical professionals prescribed Claire testosterone. And by the summer between her eighth and ninth grade years, she was lying on an operating table, undergoing a double mastectomy at the American Institute of Plastic Surgery –– a facility that, she later learned, specialized in “drains-free” procedures, which meant the surgeons did not place post-op drainage tubes in her chest after her breasts were removed. “Drains-free” procedures result in a higher risk of nipple graft rejection, a fact that had never been disclosed to Claire or her parents but Claire learned after the fact.

“I had seen the effects of a mastectomy because my mother had breast cancer,” Carrie said. “I was concerned about how serious of a surgery we were going into, and the nurse definitely reassured me that because of her age, that … she’d basically just a week later be her regular self. It was not something to be concerned about.”

Claire remembers waking up from the procedure numb and foggy. “The only firm memory I have of that time was when they first took the ace bandages and the post-op binder off, and I cried,” she said. “The people in the room with me thought that it was happy tears.”

But Claire wasn’t so sure. After all, for the past several years she had been on a cocktail of hormonal injections and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the latter of which left her feeling emotionally anesthetized.

What followed wasn’t freedom from her female reality, but devastation from her attempt to chase what she believed was the male ideal.

“Shortly after, when I started weaning off the [pain] medications, I started to realize that nothing had really changed,” she said. “Then, my nipple grafts fell off, and there were just open sores, open wounds on my chest. I felt anything but normal. I felt freakish.”

For Claire, this result was devastating and sparked months of depressive behavior. The medical professionals she trusted with her “top surgery” allegedly had encouraged her to remove her breasts between middle and high school so that she could enter high school as a boy. But it became clear this was not, and never would be, realistic.

Carrie watched as her once-vibrant daughter withdrew into herself. “I felt helpless, and I didn’t know how to help her,” she said.

Carrie’s isolation from her daughter’s pain was not just Claire’s doing. The therapists and doctors Claire had been seeing were “kind of the intermediary” between her and her child, and those medical professionals allegedly did not encourage open communication and dialogue.

Additionally, Claire said she was scared to tell her parents that she was beginning to question her transition. “I didn’t want to make them feel like they had done anything wrong,” she said.

Even after Carrie found breast forms, or bra inserts meant to emulate the fullness of natural breasts, in Claire’s room and asked her if she was having second thoughts about the surgery, her daughter couldn’t bring herself to confront the full truth.

“She got very angry and defensive and said ‘I knew you were going to say that, and that’s why I didn’t tell you,’” Carrie recalled. “What I realized is she was trying to protect me. She didn’t want me to have the regret that she had.”

Claire finally opened up about her regret when she was 18 years old and asked her mother to attend a pre-op appointment with her for breast reconstruction.

“I held my feelings in and was like, ‘Of course I will,’ but I was so confused,” Carrie said. “There was just a real huge wave of regret.”

Claire said the process for her breast reconstruction was essentially the opposite of her double mastectomy experience.

“It was infinitely harder to get breast reconstruction as an 18-year-old than it was to get a double mastectomy as a 14-year-old,” she recalled. “There was a whole long talk about, ‘Okay, this is what’s going to happen. This is what your other options are. This is your choice.’ That was never how my mastectomy was framed. It was always, ‘This is the treatment for your condition.’”

The reconstruction brought some comfort to Claire, but it could never fully heal her emotional and physical wounds. Though she’d like to be a mother someday, Claire said she will never be able to breastfeed her children, let alone feel their touch on her skin.

“Actually, I feel less than I did before the reconstruction,” she admitted.

Carrie said she has tried to give grace to the medical professionals who told her they were helping her daughter, but the deeper she reflects, the harder that becomes.

“I’m still grappling with it,” she said. “Honestly, a lot of these thoughts are very new to me because Claire has known for years that it was the wrong decision for her. But Claire didn’t share that with me until less than a year ago. So it’s just still a lot.”

For Claire, her grief over what she’s lost is now paired with conviction.

“I feel like I was allowed to make that decision before I knew what I was losing,” she said. “You tell a 14-year-old you’re never going to be able to nurse your children, and they’re like ‘Ew, babies. Gross.’”

Primarily, Claire said she places blame on the indoctrinating culture, leftist organizations such as the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH), and medical governing bodies “that decided that this was okay for children to make these decisions.”

“But when I’m ruminating on it and thinking about it, I blame my surgeon,” she admitted. “I think the primary motivation for him was money, and he didn’t care if he was helping or harming.”

As she’s detransitioned, Claire has had to confront not only the physical repercussions of medicalization, but the emotional toll it took on her as well. At first, she cycled through various labels as she tried to come to terms with the damage done to her body –– nonbinary, agender, genderfluid –– before finally arriving back at her own womanhood.

“I was always just a girl with trauma with a hard relationship with her body,” Claire said.

Carrie said she feels pride in seeing what Claire is doing now –– speaking out publicly so that others don’t go through the same pain.

“Seeing Claire take the initiative to find her own [reconstructive] surgeon, to find support from other detransitioners does make me very proud of her,” Carrie said. “She is coming into herself as a young adult with such energy and passion.”

Indeed, Carrie said Claire has a visibly renewed enthusiasm for life — a welcome change after years of watching her struggle through dark, emotional turmoil.

Claire added that detrans activists like herself, Prisha Mosley, Soren Aldaco, Chloe Cole, Cristina Hineman, Isabella Ayala, and many more advocates for reform in this area, aren’t speaking up out of hate for people struggling with their biological sex.

“We want children to grow into adults who can make informed, rational choices, who aren’t in the midst of these crises, who can look back at their history and make an informed choice, not one based on panic and emotion,” she said.

Claire added, “I did everything they told me would make me whole—and I still ended up broken. Now I speak because no child should have to go through what I did just to figure out who they are.”